History & Biology

We are keeping this section at the top as general information. Please see sections below for updates on LDD on Mazinaw.

The summers of 2019/2020 were definitely the season of the gypsy moth! While at your cottage/home you may have been inundated with a plethora of these little moths from the beginning of July until almost the end of August. The following provides some history and biology of this invasive pest.

The gypsy moth is not native to North America. The gypsy moth that we find mainly in Ontario, Quebec and the Maritime provinces was introduced into the USA around 1869 by a French naturalist attempting to cross the European gypsy moth with North American silkworms, with the hopes of creating a silk industry in North America. The native silk-spinning caterpillars were susceptible to disease so the thought was to bring over the gypsy moth eggs with the intention of creating a caterpillar hybrid that could resist diseases. Some of the moths escaped and eventually found their way into Eastern Canada.

So why is the gypsy moth a problem? They are very destructive and (as their name suggests) can travel far and wide by attaching themselves to a variety of objects. Their appetite is insatiable, mainly enjoying 500 species of the broad-leaf trees of red and white oak, poplar, and white birch with the ability to completely defoliate and kill large amounts of these trees. They have also developed an appetite for some conifers. The larvae can chew small holes in leaves or completely strip a canopy. It is estimated that during the larva stage one square metre of leaves can be devoured! Tree losses greatly impact our forests by affecting the many benefits provided by them. The destruction of oak trees greatly impacts wildlife, especially deer that depend on acorns to provide them with the necessary nutrition to survive our winters. The related forest industries are economically impacted as well. And because gypsy moths are not native, they do not have many natural enemies.

Gypsy moth infestations are cyclical, coming in waves every 7 to 10 years or so, with most infestations lasting approximately three years. The last bad wave was in the early 1980s.

With the last infestation a fungus was produced which helped to keep the population in check by causing a fungal disease in the caterpillar. This fungus requires a great deal of moisture, something we have not seen in the last couple of years. Even though we had a very wet spring this year, more wet springs are needed in order for the fungus to get established. As a result of a few dry seasons, a massive number of moths laid eggs in 2018 with the result of us seeing millions and millions of caterpillars hatching this spring.

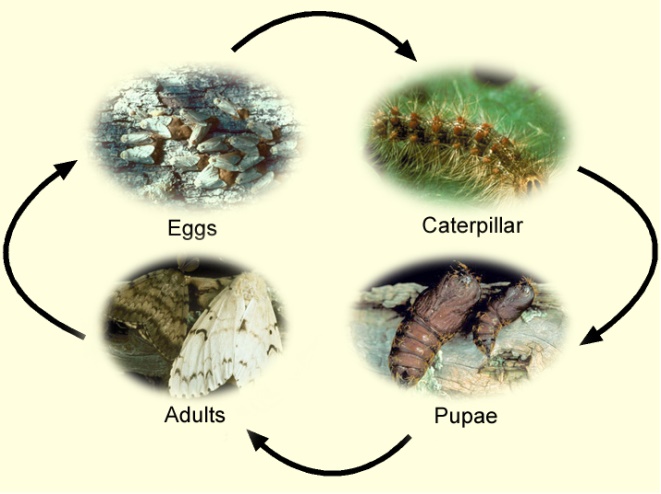

However, there are things we can do to keep this invasive species in check. First, we have to know what to look for. There are four developmental life stages of the gypsy moth: egg, larva (caterpillar), pupa and adult.

Eggs are laid in sheltered areas toward the end of summer by the adult moth. The male is greyish brown. It can fly and survives about one week. The adult male can mate with several different females during this time. Females are larger than the male, whitish in colour with darker zigzag marks than the male. The female does not fly well and will die shortly after laying her eggs.

Locating egg masses is very important in the eradication of the gypsy moth. The moth hibernates in these egg masses which may contain from 100 to 1000 eggs. The egg masses are covered with hairs tan and buff in colour. They can be found in many places including tree trunks, bark, outdoor furniture, tents, trailers, sides of buildings, the underside of branches, fences, firewood, swing sets, boats, under eaves of buildings, and many more hidden places!

The following spring, when tree buds begin to open around late April or early May, the young caterpillars emerge with their voracious appetites. The caterpillars or larvae change the way they look as they are growing. From 0.6 cm and black and brown, the caterpillar develops bumps along their backs with coarse hair as they grow. In the latter part of this stage the caterpillar is charcoal grey in colour with a double row of five blue and six red dots on its back. This stage can last up to seven weeks. The larvae spread easily by being carried on wind currents or hitching a ride on objects, thus earning the name “gypsy” moths.

After wreaking havoc on your trees for about a month, the caterpillars rest in their pupae cases. During July or August, they emerge as white or brown-winged moths and prepare to lay eggs, starting the whole process again!

Do you know what you can do at each developmental stage to rid yourself of the gypsy moth? Here are a few recommendations:

- Egg masses:

- Scrape off with a knife and burn or drop into a bucket filled with hot water and household bleach or ammonia. Do not bother to knock eggs and nests to the ground, because from there they can still hatch. The nests have to be destroyed.

- Caterpillars and pupae:

- Handpick and crush. The long hairs of the caterpillar can cause skin irritation or allergic reactions in some people. To be safe, wear gloves when handling them.

- Caterpillars can be successfully trapped. To make a trap, wrap a 45 cm (roughly 18 inch) wide strip of burlap around the tree trunk at chest height. Tie a string around the centre of the burlap and fold the upper portion down to form a skirt, with the string acting as a belt. The caterpillars will crawl under the burlap to escape the sun and become trapped. Later in the day, lift the burlap. Pick off the caterpillars and dispose of them.

- Adult moths:

- Use pheromone traps to lure the male moths. You can purchase these traps from MPOA to put around the outside of your home.

- Remove picnic tables, swing sets, and lawn furniture from around the bases of trees, because these objects provide the insects with protection from the heat of the sun.

- Be vigilant, check your equipment, vehicles, the walls of your home, etc. Know when to check and what to look for at each stage of the life cycle of the gypsy moth.

The seriousness and extent of the gypsy moth infestation in a given year can be predicted by the size of the previous fall’s egg masses, with larger egg masses (e.g. the size of a toonie) indicating stable or growing populations. If this fall’s egg masses are large, the summer of 2020 may very well be a repeat of the summer of 2019. Smaller egg masses (e.g. the size of a dime) are an indication that populations are on the decline.

September 3, 2021

Great News! We have been hearing from MPOA members that the Lymantria dispar dispar (LDD – formerly referred to as gypsy moth) invasion has subsided. Members are not seeing the expected egg masses in their trees this month.

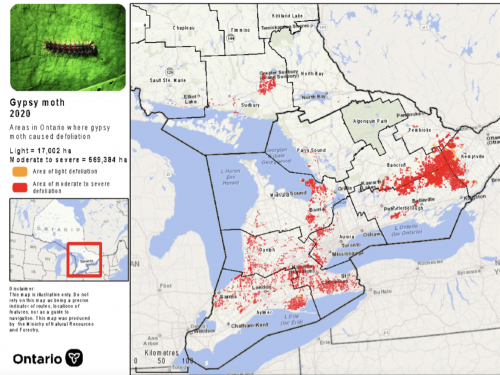

In the FOCA (Federation of Ontario Cottagers’ Associations) August ‘Elert’ there is a Newsletter from the Lake Steward. The newsletter contains a comprehensive article on LDD including the map below. We though you might find the map particularly interesting as it shows that we were at the epicentre of the invasion.

This is the link to the Lake Stewards Newsletter. Scroll to page 14 for the LDD article

FOCA_2021_LakeStewards_FINAL_web.pdf

July 9, 2021

The MPO received this email about gypsy moth traps from Ross Breen, Stone Soup Farms Ltd. of Harlowe, ON

We are all struggling with the Gypsy Moth infestation and pheromone lures for trapping the male moths are in short supply. Petro-Canada Northbrook has them available for $5+taxes. This trapping stage of the battle against this pest is crucial to knock the 2022 population down by preventing males from mating with females and decreasing the number of eggs for next year’s hatch. These lures can be used in store-bought traps or homemade.

These lures are pheromone impregnated rubber bands and were freshly made by scientists. See attached picture – Gypsy Moth Lures.

The lures can be kept at room temperature pretty much all season. If there are spares at the end of the season, then they should be triple bagged and placed in the freezer. They will easily last until next season.

Spacing - 6 traps in 1 acre. But if you have many acres, more like 4 traps for every acre. You don't want the traps too close together, because the air will become saturated with pheromone. If that happens the moths become confused, don't know where to fly to, and tend not to fly into the traps at all, so you don't catch many.

A portion of sales will be donated to The Friends of Bon Echo Park and the Canadian Wildlife Federation.

See attached picture – Yoghurt Container Trap. Trials have shown this style of trap works 10X better than a bottle trap and is easier. If you would like to see instructions for a bottle trap there are several on YouTube including this one https://youtu.be/D02_42GtcU8. You would replace the pheromone shown with the impregnated rubber bands.

www.facebook.com/StoneSoupFarms

June 30, 2021

This post was on the 'What's Happening in Northbrook/Flinton/Kaladar/Cloyne' Facebook page. It's a great summary about gypsy moths and why you should not cut down the compromised trees:

Cultivated Art Inc.

Don’t cut down any of your defoliated trees and shrubs, even the evergreens.

Observations of a forest ecosystem during an extended population boom of foliage feeding caterpillars:

Over the six years we have been spending time with the land and forest a bit west of Perth, there have been 5 years of high population of tree feeding caterpillars. The Forest Tent Caterpillars arrived first, entirely defoliating cherry, oak and big toothed aspen trees and moderately feeding on wild apple, hawthorn and a few other species.

As their population peaked and declined, the LDD (Lymantria dispar dispar / Gipsy Moth) population began their climb. Last year they entirely defoliated the oaks and aspens, and then, to my surprise, moved on to the white pines and pretty much any other plant, including herbaceous perennials and raspberry bushes.

So, what happens to a mostly forest ecosystem with this many years of heavy foliar feeding?

The oak trees have proven to be startlingly resilient, re-leafing lushly every summer. Some, minor, thinning of the interior canopy has occurred, but even the very young trees have held their own overall.

Even the white pines branches that were stripped of foliage retained their growth tips and have started filling back in nicely.

The undergrowth is where I’ve seen the most significant shift. The combination of reduced sun and moisture competition in early summer (trees without leaves cast few shadows and drink little water), with fertilizer literally raining down for a month in the form of caterpillar droppings, made for awfully nice growing conditions.

The oak sedge is incredibly thick and lush and the small patch of wild leeks has the most flowers ever.

The defoliation feels pretty traumatic. It is shocking to see the leaves disappear. Even more so to see evergreens stripped of their previously permanent foliage. But the growth tips and leaf buds remain. Healthy trees can hold out through a few years of caterpillar loading.

Since evergreens generally hold needles for 2 to 5 years before naturally dropping them, they will take about three years to look like their old selves.

The nutrients from those leaves doesn’t leave the ecosystem. It rains down to the soil, where it is captured by the undergrowth, which will, in turn, release much of it back to the trees as the canopies fill back in.

In areas where the cycle has just started, protect your evergreens next year by removing as many of the egg masses as you can find between their laying in a couple of weeks and their hatching next spring. Wrap the trunks in burlap, fold it down and then empty the resulting trap daily for a few weeks next spring.

The up side of having multiple years of high caterpillar population is that the virus that reduces their population (multicapsid nuclear polyhedrosis virus or LdMNPV) is now becoming quite established in the local ecosystem and, despite the thousands of egg masses and the tens of thousands of tiny hatchlings I saw this spring, the damage to the trees is far less than I was expecting this summer.

I’m actually seeing the highest number of caterpillar fatalities on the evergreens that had the most feeding last year. Enough that they have less feeding than the trees that weren’t munched on before, which makes me doubly glad that I didn’t clip off the defoliated branches.

May 23, 2021

Entomologist questions safety, benefits of gypsy moth spraying.

Click the link below for interview with Gard Otis, a Professor Emeritus at Guelph University.

https://www.frontenacnews.ca/.../14832-entomologist...

May 2021

Addington Highlands on the gypsy moth outbreak this spring:

Anyone who has had the time to patrol their property and look for gypsy moth egg masses will know that there are a lot of egg masses out there! The Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry did some detailed sampling across the infected zone and have forecasted that, should all of these eggs hatch successfully and develop through all of their larval stages, we should expect “severe” defoliation. Use the link below for the full article.

April 2021

The Ontario Government has an excellent web site on gypsy moth.

Our MPOA Lake Stewart - Vern Haggerty advises that there is useful information on the site. One point of interest he notes is that the Ministry is predicting severe defoliation for our district again this year. He is also hopeful that Mother Nature proves them wrong.

Fall 2021

Gypsy moth Pheromone traps

Due to the extensive Gypsy moth outbreak we are currently experiencing, the MPOA will not be offering gypsy moth traps for sale this year. Traps probably reduce the number of fertilized females when moth populations are low between major outbreaks, however they offer virtually no benefit currently.

it may be satisfying to empty a trap full of dead moths every few days during a major outbreak this does nothing to reduce defoliation. The caterpillars do all the munching, only males can fly and females are generally found on or near the trees they fed upon. Due to the number of male moths in flight last year and the expected number this year the use of female pheromone traps would do little to disrupt males from finding and fertilizing the real females.

Aerial spraying of Baccilus thuringiensis Aerial spraying by a company like Zimmer aviation is expensive (about $400 per lot up to one acre) but, if done at the critical time when eggs have just hatched around mid to late May, will definitely reduce defoliation on the sprayed area. Contracts with Zimmer are required no later than March 1, 2021. Some, including experts from the MNRF, argue that spraying may delay the emergence of some natural pests such as those listed below. For this reason and due to the expense of widespread spraying MNRF does not plan to do spraying on crown land near Mazinaw.

Natural enemies of the Gypsy moth This NPV (nucleopolyhedrosis virus) is usually the most important factor in the collapse of gypsy moth outbreaks in North America. The virus is always present in a gypsy moth population and can be transmitted from the female moth to her offspring. It spreads naturally through the gypsy moth population, especially when caterpillars are abundant. During a gypsy moth outbreak, caterpillars become more susceptible to this virus disease because they are stressed from competing with one another for food and space. Typically, 1 to 2 years after an outbreak begins, the NPV disease causes a major die-off of caterpillars.

Another natural killer of gypsy moth caterpillars is a fungus called Entomophaga maimaiga. Fungal spores that overwinter in the soil will infect young caterpillars early in the summer. When the young caterpillars die, their bodies produce windblown spores that can spread and infect older caterpillars. Large caterpillars killed by the fungus will hang head down from the tree trunk, and the bodies of the dead caterpillars appear dry, stiff and brittle. Within several days, the cadavers fall to the soil and disintegrate, releasing the spores that will overwinter back into the soil.

Destroying egg masses The best bet for management of future gypsy moth damage to your property in the short term if you choose not to spray is to remove and destroy egg masses in the late summer. Use a hand-held vacuum or scraper and collect eggs into a bucket that you fill with soapy water for 48 hours to kill them.